Everyone learns in a different way and the last thing we would try and do is foist our own preferences onto another individual. Chess is no different and what worked for one player doesn’t necessarily mean it will work for another.

In this spirit we have come up with six learning personas that your child might fit into. In all likelihood they may use elements from different personas but overall they probably resonate most strongly with one.

So what chess learning persona best describes your child?

Book Worm

Book worms are found constantly reading chess books – they can’t get enough of them! Often found playing through games in a book over the board or even just following the games in their head (a sign of great board visualisation – a core chess skill we have discussed on a number of occasions).

World champion Magnus Carlsen was a confirmed book worm as are many of the top England internationals we have recently interviewed including David Howell, Luke McShane and Michael Adams.

Boxset Binger

OK so we’re not talking Netflix but we are talking about someone who derives most of their chess knowledge from watching online videos. There is a huge selection available for free on youtube and Twitch not to mention various commercial providers such as Chessable and Chess24. This modern medium is certainly more accessible than the traditional chess book but there is an argument to say a student’s brain may be less engaged whilst watching a video compared to the more active task of following a game in a book.

Scientist

A scientist likes to perform experiments and never takes anything at face value without checking for themselves. Typically a scientist will be found experimenting on their chess board trying to find holes in the analysis they may have just watched or read – or perhaps trying to find improvements in a recent game of theirs.

Independent study and research is important and the sign of a keen enquiring mind (healthy ingredients for a successful chess player). However, the scientist must learn not to completely close themselves off from their mentors and instructional literature and strike the right balance between their own research and the work of others.

Engineer

The engineer likes nothing better than to turn their engine on and get to the truth of the matter. In chess we sometimes call switching on Stockfish “pressing the truth button” – so enormously strong it is now. Of course this is huge tool that we have at our disposal now compared to previous generations but with great power comes great responsibility.

Whilst it is true we can learn things about chess much more quickly by using an engine – for instance our intuition on how to evaluate a position, understanding tactical motifs and resources – it does come at the large cost of potentially weakening our own calculation muscles. When we turn on the engine we forgo the opportunity to think for ourselves and therefore are not practising the skill of calculation that we will so badly need during a real game.

Like with so many other things in life we need to use things in balance and choose the right tools for the right job.

Speed Demon

Another somewhat modern phenomenon – some players are getting extremely strong at chess by, it seems, playing lots and lots of very fast chess online. For example the Iranian sensation Alireza Firouzja seems to have taken this path (though to be fair he has also revealed he has read a serious amount of chess literature also).

If improvement in a discipline relies on getting feedback on your performance – then playing lots of blitz (or that truly moden opinion splitting chess phenomenon – bullet chess) makes a lot of sense as you are accumulating lots of feedback in quick succession. However this is only really beneficial if there is a fair amount of discipline involved as well and the player is able to critically analyse their mistakes. To this end we would recommend analysing evern your blitz games – even if it just to check where you could have improved in the opening.

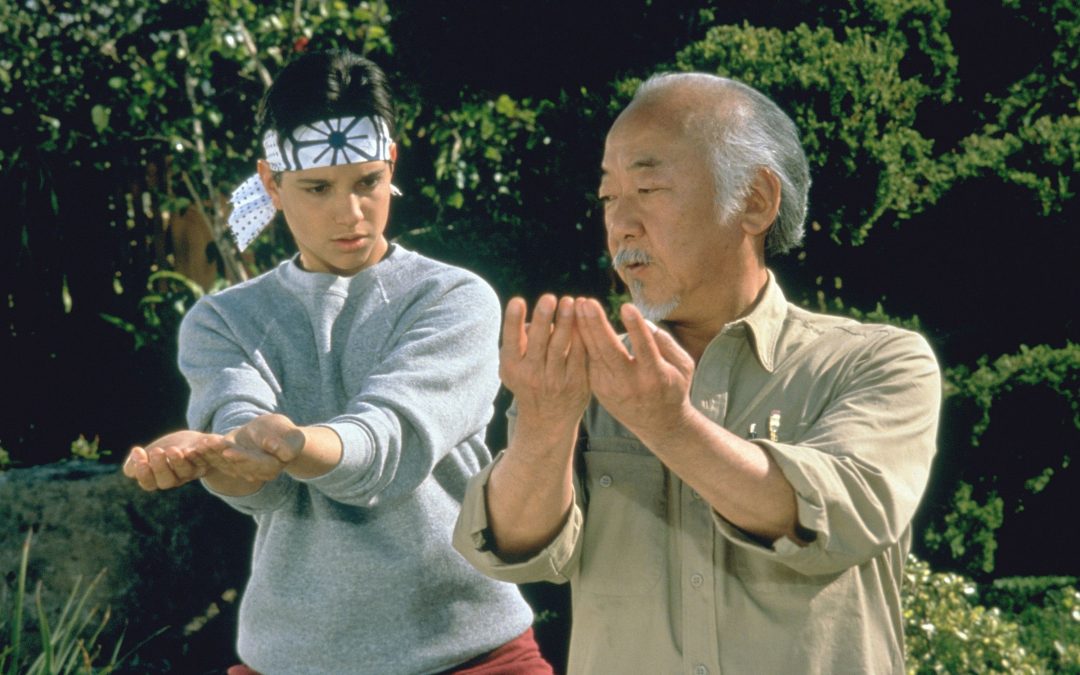

The Apprentice

Finally we have the apprentice who absorbs most of their knowledge and lessons directly from a mentor, coach or teacher (or perhaps a combination). This individual may get regular lessons or coaching sessions with little independent research away from this relationship.

Another double edged sword – there is no doubt that access to a highly skilled trainer can massively accelerate the learning process and without some support it is basically impossible to go far (as is the case in all skills based disciplines). However this should not be at the cost of losing your independence as a learner and so combining coaching with your own research seems like a great combination. At the very least the coach should set additional exercises and activities for the student to do outside of the structured lessons.

Conclusion

As we can see there are pros and cons of all the approaches and there is certainly no one best size fits all approach. However we think it is important to be aware of the potential limitations of just taking one approach and also to be in tune with the natural preferences of your child as the reality is that the more natural and enjoyable an activity is the more they will do of it! So our main tips are:

- Be aware of your child’s particular preferences

- Encourage and support them in their practise

- Be aware of the potential downsides so that they are able to mix up their practise a bit to get a good balanced approach

Ultimately a good training and practise routine should include the following:

- Be enjoyable

- Be sustainable – built on habits that are repeatable

- Be in the “training zone” – ie the edge of comfort so that the task is challenging without being so hard to be discouraging

- Allow for feedback and introspection (so let’s rule out playing 100 bullet games in a row – however a few games of blitz are fine if we then look up the opening afterwards and write down where we could improve for next time).